Vajira Pictures

by Sudath Nishantha

Vajira seventy-seven today:

|

|

|

Vajira Chithrasena |

|

Garayakuma which is a part of the low-country dance ritual was performed at the Chithrasena-Vajira Dance Academy yesterday with the participation of its students. The performance which was mainly a gesture of honour to the legendary female dancer Chithrasena was also an attempt to enable younger generation to witness those dying traditions, said Ms. Upekha Chithresena of the Chithrasena - Vajira Dance Academy. |

An encounter with such a pleasant interviewee should be the wish of every journalist! A smiling Vajira Chithrasena, Sri Lanka’s legendary female dancer who has always been able to keep her audience spellbound with her enchanting performances for several decades is right in front of me ready to share her lifetime achievements on the eve of her seventy seventh birthday!

Together with her late husband Chithrasena, Vajira could develop a strand of theatre that was stamped with local identity, but still with universal appeal.

Recalling her past, the first professional female dancer of the country says that though women had already entered the field of dance at the time she did, none of them had pursued it professionally.

“Miriam Pieris and Chandralekha were two dancers who adorned the male costume and performed on stage before me.” It was for Vajira that the first female costume for the traditional Kandyan dance was designed by Somabandu for the opening pooja sequence for the ballet `Ravana’ in 1949.

Even as a child Vajira had always been quite sociable, had freely mingled with crowds. She had also worked as a dance teacher at various schools. “But it was Chithrasena who moulded me into what I am today.”

She asserted. She admits that as a child she never aspired to become a dancer though it was her mother’s wish to see her as a dancer in future. “The interest developed only after I met Chithrasena. As I became a pupil of his and started working with him my innate ability sprang to light.”

The Kalayathana which later came to be known as Chithrasena-Vajira Dance academy was established in 1944. Prior to that Chithrasena had conducted dance classes at various places.

|

|

|

Vajira with her ‘grandmotherly’ touch at the Kalayathana Pix by Chinthaka Kumarasinghe |

From the very early days she had got engaged in all the creations of Chithrasena. The experience she gained through engaging in stage work laid the foundation for her future successes.

Initially Chithrasena being the first professional dancer himself had to face lots of stumbling blocks in persuading the society to think positively about professional dancing. “By then dance was an accepted vocation in India and also in most of the countries.”

Vajira recalled how her late husband legendary dancer Chithrasena used to visit India frequently during the period 1944-1946 collecting necessary material and meeting prominent people like Indira Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru at the Shanthinikethana.

|

Awards 1985 - Zonta International - Women of Achievement in Fine Arts 1988 - International Women’s Day Contribution to the dance of Sri Lanka 1988 - Presidential Award Kalasuri from President J.R. Jayewardene 1997 - Cultural Exhibition Award Viharamahadevi Balika Vidyalaya, Kiribathgoda 1998 - International Women’s Day from The President H.E. Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga for the Service to the Dance 1999 - Praise to the teachers who led us, Princess of Wales College Union 1999 - Vishishta Prathiba award Contribution with dedication to the Arts, Dharmaraja College Annual Cultural Exhibition. 1999 - Yuganthaya New Millennium Award Independent Television Networks for the Contribution to the Dance of Sri Lanka Vinodhan Ninaivalayam Cultural Award `Sinhala Ballet 2001 - International Women’s Day, Sharma Shakthi Union Award, Contribution to the dance |

But When Vajira started her career in 1946, the society had undergone many changes. “Dancing was not viewed with scorn any longer. Public had begun to accept it as a profession and it was also added as a subject in school curriculum.

In fact the elite in Colombo too had started paying attention to the subject. It became a fashion at that time to learn the national dance. “Following her marriage to her Guru Chithrasena in 1950 it became more of a team work. They started performing together.

|

|

|

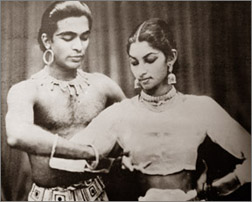

Vajira and Chithrasena |

“Whatever we created it was based on traditional dance. Chithrasena is the only one who had always maintained the tradition in the background. It was Chithrasena who pioneered the creation of stage dramas.

Also it was he who made women to take up to dancing. Earlier performances like Kohomba Kankariya and Gammaduwa were performed overnight. It was Chithrasena who brought those traditions to the stage making them a refined art.

“There was a story behind all his creations. Earlier it was just a dance. It was Chithrasena who mooted the idea of developing a dance with a story behind. But he was always very careful not to violate any of the traditions.

Adding another feather to her cap Vajira became a choreographer at the age of 20 by producing the first children’s ballet named “Kumudini” in 1951. “Children never participated in ballets before that. The story which was written by Ananda Samarakoon revolved around a flower and a bee! In fact it was a dialogue between “Kumudini and bees” she smiles.

As I put to her the most frequently asked question- of her ability to assimilate modern techniques into Sri Lankan traditional dancing, she tells me that there is `no such thing called modern dancing.’ With time and experience choreography becomes more stylised.

As we practise dance for a long time we get the opportunity to find more ways of interpreting it. “All that depends on one’s creativity. You can make any traditional dance look different and novel if you are creative enough. You can do that without violating traditional rules.”

She adds that such creativity is a must. Then it is easier to express your ideas to the audience . Unlike in Indian dances `hand gestures’ are not used in Kandyan dance, So it becomes necessary to make use of many artistes for our performances.

She says that moulding the art the way dancer wants is his or her talent. “Karadiaya” was a fine example of such creativity.

|

|

|

Vajira in the mid forties |

It was Vajira who introduced feminine touch to Kandyan dancing. “I always imitated Chithrasena in all what he did. But when I displayed it to the public I did it in a `feminine’ way. Not that I changed any steps or style. It became graceful because it was done by a woman. “As she says male aspect was more stronger.

We all agree with what Bandula Jayawardena had said about Vajira’s dancing in 1986.” I think vajira mainly as the artiste through whose dance of Gajaga Vannama I came to know the meaning of grace in Sinhala dance. I believe it was she who created out of this traditional thandava dance lyric a lasya dance of delicate beauty.

The Gajaga vannama was originally danced by men. The majesty of the elephant they were expected to reflect was essentially masculine. Vajira, taking nothing away from that, added to the dance-poem a feminine grace and refinement that transformed it into a piece of presentable on the international stage. She took an unpolished gem and presented it as a perfect jewel.”

Vajira, a contented mother of three and a grandmother is still the Chairman of Chithrasena-Vajira Dance Academy. Both her daughters Upekha and Analika have followed the footsteps of their legendary parents.

It is Upekha who heads the Academy now. “My granddaughter is also involved with the administration of the Kalayathana”. I see her eyes lighting up as she speaks of her granddaughter. A contented life. Her story is a legend, would set an example to women of all calibre. We wish her health, wealth and more happiness in the coming years!

Queen of Lankan Ballet Vajira turns 75 today:

|

|

A LIVING LEGEND: We all are creatures of the sea. The ocean, the primordial fountain of life, lives in us all. It gives life to art and artists through the ages have paid homage to the ocean.

The lights go down, the sea roars in the distance and the silhouettes of human figures appear on the dark ‘horizon’. As the lights slowly regain their full luminescence, the ‘seashore’ begins to appear.

Human figures start swinging back and forth gesturing the tedious task of pulling ‘madel’. A woman moves on the stage briskly enthralling the audience with her facial gestures and swift but subtle hand movements.

The protagonist gracefully turns and swirls, flutters and trembles. She transcends cultures, humanity and age. She is the fisherwoman, swan, deer or mermaid. And the audience catches a glimpse of the virtuoso dancer Vajira.

The curtains come down. The loud applause of the audience reverberates, transcending time and space.

The wedding photograph of Vajira and Chitrasena |

Vajira performing in Kinkini Kolama |

A scene from Karadiya |

Vajira’s fine movements, gestures, rhythms and costumes have held audiences spellbound for over six decades.

“I danced for about 60-65 years. I started professional dancing when I was 15,” Vajira recalls.

Vajira, the name which always blends with Chitrasena and Sri Lankan ballet dance tradition marks her 75th birthday today. “I love to be called a teacher than anything else as I started my journey as a teacher and I still am,” the Queen of Ballet remarks with a humble smile on her face.

She first taught children’s ballet under Chitrasena who was at that time creating and experimenting a unique dance form - Oriental Ballet. The new tradition embodied features of the ancient sokari, gammadu and kolam traditions while having the Kandyan dance tradition as the base.

Vajira incorporated her ideas and efforts to carve Chitrasena’s all-time dance masterpiece Karadiya and Naladamayanthi. Her ingenuity and the passion for dance made her the first professional female dancer in the country.

“It was a significant breakthrough then as no women engaged in dancing professionally. I was the first to take up the challenge. Chitra was my guiding star and the pillar of strength.”

Sri Lankan society warmly welcomed the female access to the stage as Chitrasena had already spurred a revolution in Sri Lanka’s dance arena. Despite all his theatrical innovations in the dance form, Vajira is his greatest discovery.

“I’m a pure Sri Lankan product. I never went out of the country to learn dancing. I mastered authentic Sri Lankan traditions,” she says with pride.

She helped Chitrasena on composing and putting everything in order. While playing in Chandali she created Kumuduni. Subsequently, the pageant of Lanka, Himakumariya, Sepalika, Kindurangana (mermaid) and Nirthanjalee came alive in the form of dance drama.

Initially she was not given lead roles. “I played the deer in Ramayanaya in which Chitrasena played Ravana. I was the swan in Naladamayanthi,” she says.

In Chandali she played the lead role for the first time. Out of all dance dramas performed over decades Vajira still craves and ardently recalls the swan in Naladamayanthi.

“I fondly remember the swan as it could fly and was not a human character. That’s why it is my favourite. My figure suited that character well as it had a lot of fluttering movements,” Vajira says. Her upbringing also played a key factor in bringing her success on stage. She was born in Kalutara, where the prominent bo-tree and the dagaba are located.

“The cultural and religious upbringing later penetrated my compositions as well. Most of the stories have a morale behind them. They always propagate peace and harmony and elevate humanity,” she remarks.

Chitrasena and Vajira initially included one song in their ballets but later departed from that and built a unique form by narrating the whole story through gestures and movements.

“There are only certain things you can depict through dance. When choosing a theme it is very important to realise our constraints. That’s how stage craft becomes important in dance drama. Music is vital as it adds to the mood. I believe a good artiste can perform without music. Chitra introduced universal hand gestures to dance drama”.

Vajira has won many awards including Kalabhoosha and Kalasoori. She has travelled in many countries and performed before many distinguished persons.

“He was my inspiration. At times I wanted to show off and challenge. We always had arguments. But he is a great creator and the future generation too will follow his art. That’s my utmost wish,” Vajira comments. Their children and students have already undertaken that noble duty to take the tradition forward.

Vajira is quite dismayed by the televised dances which have emerged recently. “Commercialisation is a symbol of the deterioration of art. I’m proud that my children and students have not fallen into that stream. My granddaughter Heshma is very devoted to preserve the tradition. Her house has become an open dance school for our young dancers, “ she says with gratitude.

The art of dancing is literally not still. It grows and branches out. So are its followers. But it is as ageless as Vajira-Chitrasena and their priceless gift to Sri Lankan art.

Doyen of the dance

“To follow without halt, one aim; there

is the secret of success. And success?

What is it? I do not find it in the applause

of the theatre. It lies rather in the

satisfaction of accomplishment.”

-Anna Pavlova

A swan she was, conniving to bring Nala and Damayanthi together, a Chandali and an exploited Sisi. Following her heart’s desire in diverse roles, leaving behind her ‘dancer’s footprints’ where no sands would conceal, is Vajira Chitrasena. The Nation shares some of life’s ‘rhythmic moments’ of this legendary dancer

By Randima Attygalle

Q: Can you recollect the ‘dancer’ in you as a child?

A: I was involved in dancing initially at school

level, first at Kalutara Balika Vidyalaya and later at Methodist College,

Colombo. I started learning dancing professionally only after I came under the

wings of Chitrasena, who was my dance guru first, before he became my life

partner! Although I do not hail from a dancing background, I have creativity in

my genes, which I inherited from my mother who was artistically bent. She used

to sew all the costumes for our productions, which were designed by Somabandu.

My mother was very keen that I pursue dancing and it was she who introduced me

to Chitrasena’s dancing when I was about 15 years old. I was a very mischievous

girl and at times used to run away from dancing lessons and my mother used to

drag me back (chuckles)!

Q: How did Maestro Chitrasena mould you into a professional female dancer?

A: Chitrasena used to be a family friend of ours, even before I started

learning dancing under him. He was the one who made me think seriously about

being a professional dancer. He encouraged me to get an insight into

world-renowned dancers like Pavlova by reading extensively about them. Even my

feelings for art and culture got kindled because of him. Legends in the music

field such as Ananda Samarakoon, Pandith Amaradeva, Sunil Santha used to

frequent his home quite often and I was inspired by their work. At the same

time, I was exposed to the life of an artiste, which I consider to be my real

education in the filed. Eventually, I was emerged into the work and life of

Chitrasena. He also made me realise that dancing could be a career for females,

that one need not be clad in the ‘male costume’ on stage. Dancers like

Chandralekha used to perform in the traditional male costume, but Chitrasena

wanted to break away from it and he wanted the female dancers to project their

identity. He moulded me into a professional female dancer of dedication and hard

work and created the background required for such moulding.

Q: Can you recollect the

performances in your ‘formative years’ and your early productions?

A: Pageant of Lanka, which was a cultural festival,

organised to mark the Independence of Sri Lanka was a break-through for me as a

dancer. I can actually call it my debut as a dancer. I was quite young at the

time when I played the role of a deer in Ramayanaya. By this time, I had given

up schooling and was pursuing serious dancing. My maiden ‘human portrayal’ was

in Chandali which was an important adult role. Hitherto this I was always

playing ‘deer’ or ‘swan’ or some kind of a creature. However, the transformation

came quite naturally to me. I never had to strive hard to adapt to my new roles.

It was a systematic training I received under Chitrasena to play more demanding

and more mature roles. By the time of Karadiya, I was a very seasoned dancer. In

that ballet, I played the role of a down-trodden woman from a fishing community,

which was quite a challenging role. I was also a teacher of dancing by this time

and Chitrasena gave me freedom and support to evolve a style of my own through

my own productions. I started with small-scale ballets such as Kumudini and

Nirasha which had the musical touch of none other than Ananda Samarakoon. These

were followed by longer ballets such as Himakumari, Sepalika and Kindurangana.

Q: The name Vajira and Sri Lankan dance is synonymous. How did you carve a

niche as a dancer with a different touch?

A: It is essentially by giving our dance a ‘feminine touch.’ Although there

were female dancers before me, they were more or less portraying the ‘man’ on

stage. I think I was responsible for the ‘fluidity’ and ‘grace’ in our dance.

It’s not that I changed our tradition. Our success is the very fact that we

based our roots on tradition. However, I gave the techniques such as bar

exercises, jumps and turns a different interpretation, to make them more

artistic and more innovative. For this purpose, I went into the depths of

dancing. I wanted to make the female dance more ‘curvaceous,’ and more gliding.

I introduced a lot of ‘ground work’ for dancing in the form of exercise to make

the learning process more interesting and less taxing.

Q: What helped you balance your roles as a mother and dancer?

A: My family played a big role in that aspect. When my children were young,

they were left in the good care of my mother and my sisters, whenever I

travelled abroad with Chitrasena. They were my source of strength. We were

globe-trotting quite often and I have performed almost all over the world

including Europe, USA, Russia, Australia and so many other Asian countries. A

lot of female dancers give up their careers specially after becoming mothers,

which I never did. I danced everyday of my life and at the same time, I was

there for my children. I am so proud to see my children and my grandchildren

taking after myself and Chitrasena. I feel blessed in that way. I think it is

their judgment of what the two of us did, that matters most. They admired their

parents together on stage, which is something unique for any child to witness. I

never wanted to push my daughters Upeka and Anjalika into dancing – it was their

choice to follow in my footsteps. Even my son Anudaththa took part in our

productions when he was young. However, he became a cricket enthusiast during

his student days at Royal College and Chitrasena gave all his support to develop

his talent. He was available not only for our son, but for the entire cricket

team.

Q: What gives you the greatest

satisfaction in life?

A: I derive immense satisfaction by watching those who

have reaped the fruits of my ‘dancing labours.’ My children, my grandchildren

and my students have taken forward the legacy. I feel proud to witness their

creations today. I have had many gifted students and I have unearthed a lot of

new talent as a teacher, all of which give me a lot of self satisfaction. I have

imparted my knowledge free of charge to underprivileged students who have

displayed the talent to be promising dancers. Some of them could not even afford

the bus fare to attend the class, which I myself used to provide for them. I

remember my friends with gratitude, who came forward to assist me in this cause,

especially by sponsoring these children.

Q: What elements do you identify as the cornerstones of a successful dancer?

A: I think they are commitment, patience and hard work. If I have reached

some higher pedestal as a professional dancer, I owe it to these three facets. I

took the road very slowly, yet steadily. Patience is very important and so is

vigorous training. A dancer’s body has to be well tuned to different styles and

movements, for which daily practice is essential.

Q: How would you like to perceive your journey as a dancer to date?

A: (Smiling) I must say, I created avenues for the female dancers in this

country at a time when there were no female role models. I was never exposed to

professional female dancers as a youngster. Today people look up to me as

someone who kept the tradition in dancing alive in the country. They admire my

work and I feel appreciated. However, I never clamoured or strived hard for

personal glory. Things just came my way, which I accepted very neutrally. I was

never over ambitious. However, I was very optimistic all the time. I believe

that I cultivated the same beliefs in those who passed through my hands over the

years. Although I am a great grandmother today, I feel very much young at heart,

because I deal with young people all the time and they keep me ‘evergreen’!

Q: Is there more than the ‘dancer’ in you?

A: (Smiling) Yes, there is. I’ve got a spiritual side as well. I meditate

quite a lot and that has helped me to become an unruffled person. As a young

teacher I used to be very forceful with my students, to get the best out of them

of course. Yet, once I started meditating, I became quite a different teacher

and a different person as well. It helps me to look at life in a different

perspective.

(Pix by Pushpakumara Mathugama)