Sri Lanka Genealogy Website

Federalism & the Kandyans

By Charitha Ratwatte

– Colombo

At the time the Kande Uda Rata Rajadhaniya was ceded to the

British Crown in 1815, it consisted of, 21 Divisions, of which the 12 principal

ones were called Disawani and the rest, Rataval.

The Disawani were (1) The Four Korales, (2) The Seven Korales, (3)

Uva, (4) Walapane, (5) Udapalatha, (6) Nuwara Kalaviya, (7)Matale,

(8)Sabaragamuwa, (9)The Three Korales (10) Wellassa, (11) Bintenna, (12)

Tamankaduwa.

The Rataval were: - (1) Udunuwara, (2) Yatinuwara, (3) Tumpane,

(4) Hewaheta, (5) Uda Bulatgama, (6) Kotmale, (7) Harispattu, (8) Dumbara, and

(9) Pata Bulatgama.

The colonial administration ruled the island in three distinct

parts, three ethnic based administrative structures, Low Country Sinhalese,

Kandyan Sinhalese and Tamil.

In 1829, the British established the Colebrooke-Cameron Commission

to review the colonial government of

(1)

Central

Province- consisting of the central Kandyan Disawani of Uva (upper part),

Walapane, Uda Palatha, Matale, Three Korales, Bintenna, Tamankaduwa and the

Rataval of Udunuwara, Yatinuwara, Tumpane, Hewaheta, Uda Bulatgama, Kotmale, Harispattu

and Dumbara

(2)

(3)

(4)

Southern

Province- composed of the Maritime Districts of Galle, Hambantota, Matara and

Tangalla, and the Kandyan Disawani of Uva ( lower part), and the Disawani of Sabaragamuwa and Wellassa,

(5)

Western

Province- composed of the Maritime Districts of

The Kanda Uda Rata Rajadhaniya was thus dismembered.

Further dismemberment took place when in 1845 the North Western

Province was carved out of the Western Province, the Maritime Districts of

Chilaw and Puttalam and the Kandyan Disawani of Seven Korales.

In 1873 the

In 1886 The Uva Province was created from parts of the

In 1889 the

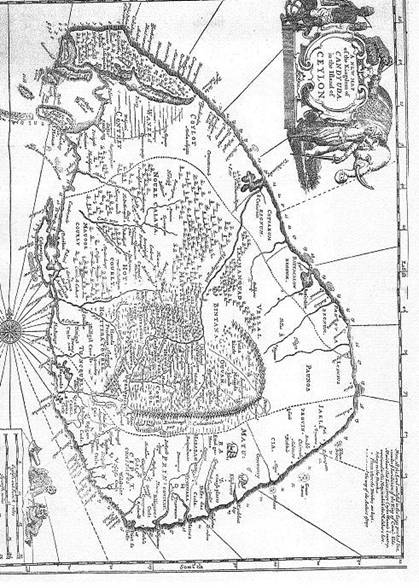

Map from,

Robert Knox.

Captain Robert Knox in his book a Historical Relation of Ceylon

published in

While administratively the distinct Kandyan identity was

disaggregated in this manner, on the aspect of the Kandyan Law there was a

similar dilution. The proclamation of the Kandyan Convention of 2nd

March, 1815, clause 4, provided that ‘….. Saving ….to all classes of people

……..their civil rights and immunities, according to the laws, institutions, and

customs established and in force amongst them.’ In terms of this the

Kandyan law applied to all persons living within the Kandyan Provinces. In the

case of Mongee v.Siarpaye, in 1820,

the Board of Commissioners which adjudicated disputes in the Kandyan Provinces determined

that a form of marriage peculiar to Kandyan Law, Binna marriage, applied to the

case, although both parties were Muslims. Similarly in Kershaw v. Nicoll the Supreme Court held the Kandyan Law should be

applied to all litigation in the Kandyan Provinces. However, this was overruled

by the full bench of the Supreme Court in William

v. Robertson, in 1886, which held that Kandyan Law was a personal law

applicable to Kandyan Sinhalese only. The

outreach of the Kandyan Law to all residents of the former Kande Uda Rata

Rajadhaniya was thereby diluted.

The Waste Lands Ordinance of 1897 declared that in affect all

lands for which there was no legal title which could be proved was waste land

which vested in the Crown. In the Kandyan Provinces only Buddhist religious

institutions and those others who had received Sannasas from the Kandyan King,

who owned all lands in the Kingdom, could produce such title documentation.

Common village land was held and cultivated in terms of common custom and practice.

All such lands were appropriated by the Colonial government and sold for a

pittance to British colonial officials, business men, Burghers and Sinhalese from

the

The Moslems living in the Kande Uda Rata Rajadhaniya had also some

unique features. Frank Modder in his Principles of Kandyan Law (1914) wrote

about the Kandyanized Moors and the fact that they married in terms of Kandyan

Law and that Mohammedans perform

But in 1852 the Mohammedan Code was extended to Muslims living in the

Kandyan Provinces in all matters between themselves.

At one time Federalism was seen as a system of government which

would help the Kandyan people and other ethnic groups to preserve their

identity, distinct customs and life style, while living in one nation with

multiple ethnicities.

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, speaking in

In 1927 the colonial government appointed a Commission, chaired by

Lord Donoughmore, to report on the situation in

The Commissioners responded to what they called the Kandyan Claim

in a separate and distinct chapter of their Report. They expressed sympathy for

the concerns expressed by the Kandyan Sinhalese but rejected the claim for a

federal Ceylon mainly on the basis that the country needed to be united, ethnic

and regional identity needed to be transcended and that what was most important

at his stage of Ceylon’s constitutional evolution, leading towards independence

from Britain, was a philosophy of a united Ceylonese mentality.

In 1938, British colonial civil servant, Leonard Woolf, who had

served in Ceylon, in the district administration, in Kandy, Jaffna and

Hambantota, and therefore had worked with all communities and in all

geographical regions of the country, based on his experience, proposed a Swiss

model C

However none of the proposals to protect the unique and

traditional culture and nature of the Kandyan people and other ethnicities ever saw

fruition .

Notwithstanding this dilution of the Kande Uda Rata Rajadhaniya

and the resultant alien influences, to this day the Kandyan people have been

able, with much difficulty, to maintain a unique identity and in some cases as

in marriage, Buddhist and other traditional cultural rituals spread their

customs to the Sinhala people living in the former

The difficulties and travails faced by the inhabitants of the

Kandyan Provinces, in 1951 led the government of the day to appoint the Kandyan

Peasantry Commission to obtain an overall picture of the social and economic

life of the Kandyan Peasantry in what can be described as the Kandyan heartland,

the Central and Uva Provinces, most affected by the development of the

plantation economy, and to ascertain the measures that should be adopted to

ameliorate their conditions. The particular matter specifically looked at were:

- land holdings, housing, education, communication, medical facilities,

employment –both agricultural and non agricultural and benefits under social

Notwithstanding the pious hopes of the Donoughmore Commissioners,

the unitary nature of the 1948 Soulbury Constitution, the 1972 Republican

Constitution, the 1978 Executive Presidential Constitution, the Provincial

Councils created by 13th

Amendment to the Constitution of 1987, this

philosophy of a united Sri Lankan mentality has clearly not yet evolved.

The obvious larger than life evidence of this are the numerous

efforts, through Sri Lanka’s political history, to solve the governance issues arising from a

multi ethnic mixture of ethnicities.

The Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kadchi

at its first National Convention in April 1951 articulated the desire of the

Tamil people for a federal union with the Sinhalese. In 1957 by the

Bandaranayke –Chelvanayagam Pact, the Federal Party agreed to accept proposals

for establishing Regional Councils as a first step to achieve its political

goal of a federal state. The Pact was later unilaterally abrogated.

Next in 1965 was the Dudley

–Chelvanayagam Pact. This was negotiated before the 1965 General Election an

entered into soon after the election. Its purpose was to deal with certain

problems of the Tamil speaking people and to ensure a stable government after

the election. The Pact was abandoned after three years without any progress

being made.

In 1970, Parliament acting on a mandate to enact a new

constitution received at the general election, functioned separately as a

Constituent Assembly to debate and adopts a draft constitution. The Federal

Party submitted proposals to the Assembly in the form of a Memorandum and a

Model Federal Constitution. The Memorandum proposed five separate units, (1)

the Raja Rata, (2) the Kandyan provinces of Uva, Central and Sabaragamuwa, (3)

the Southern and Western Provinces, (4) the

This was followed by the

TULF adopting its Vadukkodai Resolution in May 1976, which marked the

commencement of the struggle for the establishment of a separate state of Tamil

Eelam. This Resolution marked the commencement of the struggle for the

establishment of a separate state of Tamil Eelam. While there have been many

demands for Tamil independence before, this Resolution articulates, in the

clearest terms for the first time, the demand for an independent state for the

Tamil Nation based on their historical habitation of the Northern and Eastern

Provinces. The assassination of Alfred

Duraiyappah, Mayor of Jaffna by the LTTE in that year, signaled the start of a

war which would end only in May 2009.

After 1976 there were several attempts at solving the issue. On was

through Decentralization – the District Development Councils Act of 1980, which

also failed. Subsequent to the 1983 riots, an Indian diplomat G. Parthasarathy

negotiated an arrangement by which this existing District Development Council scheme

was to be converted into a Regional Council scheme. There emerged broad

agreement on what Parthasarathy negotiated between the GOSL and, TULF and CWC,

except on the issue of the merger of the Northern and

Subsequently, after the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh

bodyguards, there were two meeting between the GOSL, the TUNF and the militant

groups at

- Recognition

of the Tamils of Sri Lanka as a distinct nationality.

- Recognition

of an identified Tamil homeland and the guarantee of its territorial

integrity.

- Based

on the above, recognition of the inalienable right of self determination

of the Tamil nation.

- Recognition

of the right to full citizenship and other fundamental democratic rights

of all Tamils, who look upon the island as their country.

These four Thimpu Principles have since been the cardinal

principles with regard to a negotiated settlement to satisfy Tamil aspirations.

These principles contain concepts and terms which were ambiguous,

vague and had no clear or fixed legal meaning.

They could be interpreted to mean a separate independent state or only

substantial autonomy within an existing

nation state.

The government delegation, through its leader, H.W. Jayewardene

Q.C. rejected the first three principles on the grounds that they necessarily

implied the destruction of a united

In 1987 the GOSL took a more aggressive military position and Vadamaratchi

in the so called LTTE heartland was captured. The Government of India was

alarmed and pressurized the GOSL to stop its military campaign and enter into

the Indo-Lanka Accord of July 1987. This agreement resulted in legislation, the

13th and 16th Amendments to the Constitution and the

Provincial Councils Act no.42 of 1987. This step did not settle any issues, and

the constitutional conundrum and the on / off war continued. There were

sporadic attempts to sort out the problem- a Committee Chaired by Member of

Parliament Mangala Moonesinghe (1993), the GOSL’s proposals of 1995, 1996,

1997, and 2000.

After the Parliamentary elections of 2001, and the Cease Fire

Agreement, after a conference at Oslo, Norway, there was an Oslo Communiqué of 2002-

in which it was said that ‘the parties

agreed to explore a solution founded on the principle of internal self

determination in areas of historical habitation of the Tamil-speaking people,

based on a federal structure within a united Sri Lanka.’ However the complications of

In 2003 the GOSL made a proposal for Provisional Administrative

Council, in 2004 the LTTE proposed an Interim Self Governing Authority for the

North East.

After the disastrous Tsunami of 2004, the GOSL proposed a Post

Tsunami Operational Management Structure (P-TOMS). However the Supreme Court,

on a petition filed by the JVP MP’s, held that the provisions of the P-TOMS

violated the constitution on the aspects of Parliaments control over

expenditure.

In 2006 the GOSL summoned an All Party Conference (APC) to design

a political settlement to the ethnic conflict. This APC established an All Party

Representative Committee (APRC). The GOSL also appointed a Panel of 17 Experts

to assist the APRC. The Experts called for public proposals and over 700 were

received. But the Experts were split and in December 2006 released a Majority

Report and Minority a Minority Report.

Among the proposals in the

Majority Report, an innovative one to establish an Autonomous Zonal Council

(AZC) in the Nuwara Eliya District and a ‘non territorial Indian Tamil Cultural

Council ‘(ITCC) for the Tamils of Indian origin. However the Minority Report only

suggested a Department for the advancement of Tamils of Indian origin.

IN 2007, on January 8th, the chair of the APRC, Dr.

Tissa Vitharna, issued a report which he claimed was a synthesis of the

Majority and Minority Reports. On Indian Tamil Affairs he proposed that there should be a Cabinet

Minister at the Centre, a Provincial

Minster in the Central, Sabaragamuwa and Uva Provinces, supported by a non

territorial assembly consisting of the MP’s, MPC’s and some nominated members .

In May 2009 Velupillai Prabhakaran and the top rankers of the LTTE

were killed.

On January 26th, 2010 the people of Sri Lanka elected a

new President. The people of the Kandyan Provinces voted in large numbers for

him.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

At this time when our constitutional development is on a threshold

of a new era, the Kandyan people are surely entitled to a special arrangement

which will help them to nurture, preserve, strengthen and develop their special

characteristics, customs, rituals and traditions they have protected over

centuries.

The proposals in the 2007 Tissa Vitharna Report to the APRC, come

to mind, where under paragraph 13:- ‘Meeting

the Aspirations of the Indian Tamils, under paragraph 13.5:- All members of Parliament and Provincial Councilors from the

different Provinces, belonging to the Indian Tamil Community shall be members

of the Indian Tamil Cultural Council(ITCC). In addition there shall be five

nominated members. All members of the ITCC shall be appointed by the President

of

It is proposed that a similar Council, should be established by

the Constitution, called the Kande Uda Rata Sanvidhanaya be

created for the Sinhala and Muslim representatives elected to Parliament and

the Provincial Councils from the 12 Disawani and 9 Rataval constituting the

Kande Uda Rata Rajadhaniya, as at 1815, in addition the Diyawadana Nilame of

the Dalada Maligawa, the Basnayake Nilames of the Satara Dewales, at

Senkadagala Kande Mahanuwara, the Maha Kataragama Devale in Uva and the Saman

Devale in Ratnapura, should be ex officio members. The Higher Appointments

Commission, proposed by paragraph 6:1 (d) of the Tissa Vitharna Report should

appoint five other persons of repute and eminence, three of whom shall be women

and three under 30 years of age, on to the Sanvidhanaya, from among voters

resident within the limits of the Kande Uda Rata Rajadhaniya as at 1815, to

whom the Kandyan Law applies, as defined in s.11 of the Kandyan Scholarship

Fund Act no. 25 of 1971.