A

conversation with Subbiah Muthiah

On

the excavation of heritage

by Malinda Seneviratne

Human beings can be enamoured

with the past to the point of obsession. The question, "Where did we come

from?" is however not necessarily the private property of the obsessive.

The pursuit of history is also about discovering the present and locating self

in a certain temporal context with a view to be on a better footing in the

matter of imagining and designing futures. The search for and (re)discovery of

heritage, then, is at once the pleasure of a neurotic and the delight of the

pragmatic. And so, in the commerce of heritage, one finds two-bit politicians as

well as accomplished scholars, citizens of the earth who can be patriotic

without being racists. Subbiah Muthiah belongs to this second and illustrious

breed, and he needn’t have written "The Indo-Lankans: their 200-year

saga" to prove the fact.

As a young man, Muthiah was interested in engineering. Then he switched to international relations in which discipline he got a masters degree. He chose to decline a career in the foreign service, preferring to join the Times of Ceylon. From then on it was journalism, or more accurately writing in a broader sense, that occupied the man. Essentially a features man, Muthiah was responsible for the newspaper’s supplements and the Times of Ceylon Annual, the most sought after glossy publication for overseas gifting at the time. An enumeration of the various posts he held, both here and overseas, would run into several paragraphs. Suffice to say that Muthiah was a pioneer wherever he went, launching publications and numerous organisations devoted to excellency in expression, writing in particular.

Through all this, whether in the Times of Ceylon, The Hindu or the fortnightly Madras Musings, runs one indelible and delicately drawn line: heritage. In fact he’s the author of 16 books dealing with historical background, mostly centred on Madras. Muthiah firmly believes that all the key ideas of modernity have their origin in South India. Madras, for him, is the city from which modern India grew. It is in those terms that he approaches "heritage". "Madras Musings" for example, focuses exclusively on heritage issues. His extensive scholarship has made his a world authority on this geo-cultural space, which naturally spills out of the crass boundaries that describe a city and a state.

"The Indo-Lankans", Muthiah points out, covers not the confused and confusing histories over which conflict have been and are produced and maintained, but a specific period; post-1796. It is the story of the toilers, traders, professionals, players, entrepreneurs, the faithful and devout, and the leaders, and indeed this is the order in which he has chosen to allow his narrative to unfold. It is a story that is woven around 850 pictures, most of which are themselves historical.

Offering a nutshell-version of a gleaning of the past, would do both the past and the documentation at hand injustice. That the book has been commended as a seminal contribution to literature in the field, says it all. If any elaboration were necessary, one could quote the former High Commissioner for India in Sri Lanka, Gopalkrishna Gandhi: "Metaphors crowd the mind when one thinks of the diversity of Sri Lanka. But metaphors should not become a substitute for a cogent narration illustrating the story. This book achieves that goal admirably. If the text is gripping, the photographs area a visual repast.. More than the story of a people, the story of an epoch is covered in this pictorial narration - an epoch wherein a nation has been helped to attain the fullness of a padakkam studded with gems, both indigenous and from the ancient land that lies across the Mannar shore."

Gripping as the story obviously is, the tale of the story-telling is as fascinating, I found when I spoke with the author.

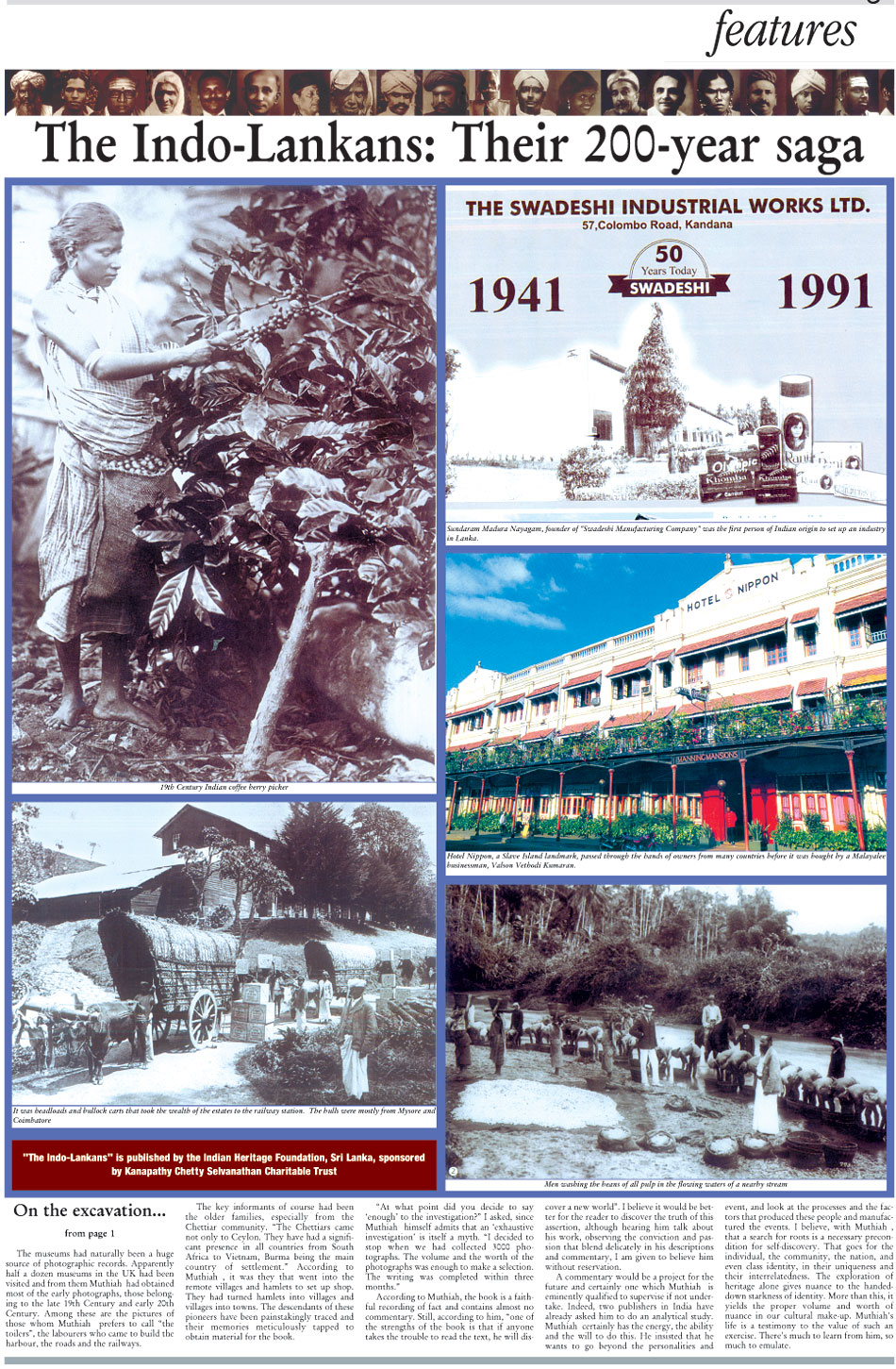

The idea for the book had been mooted by Gopalkrishna Gandhi about four years ago. "I had just completed a coffee table book on the Chettiar community, documenting their history, customs etc. Gandhi had been instrumental in putting together a book on Indians in South Africa and he was keen on a similar production on Indians in the island."

Muthiah , sensitive to the problems of terminology and identification (self and otherwise) embedded in the problematic descriptive "Ceylonese/Sri Lankans of Indian Origin", coined the term Indo-Lankans, preserving the element of origination without violating the overriding Sri Lankan signature that resides in their identity. Anyway, Gandhi had recognised that Muthiah was eminently qualified to undertake the assignment, not only because "heritage" was his thing, but on account of his scholarly rigor, passion for the subject and the fact that his life is more or less equally divided, geographically speaking, between the two countries.

"The timing was right. I was interested and also, it so happened that the Indian Heritage Foundation had also been started around the same time. The Foundation wanted to take it up as its first project. It was completed in 18 months."

Simple? Not exactly. Sure, Muthiah , having worked at the Times of Ceylon and being very well acquainted with the older Indian families living in the island, knew where to look. But advertisements soliciting information had produced nothing.

"I hired a team of 7 researchers, 4 in Sri Lanka, 2 in India and one in the UK. I worked out a framework and identified people for them to contact. It was like a detective story. You start with one clue and it leads to others and then snowballs."

That was a scenario he was not unfamiliar with. "My first book on Madras, ‘Madras Discovered’ contained 160 pages. The second version/edition, ‘Madras Re-discovered’ went into 500 pages. The third edition will be out soon and it will be even more voluminous!" Heritage excavation is never completed, obviously.

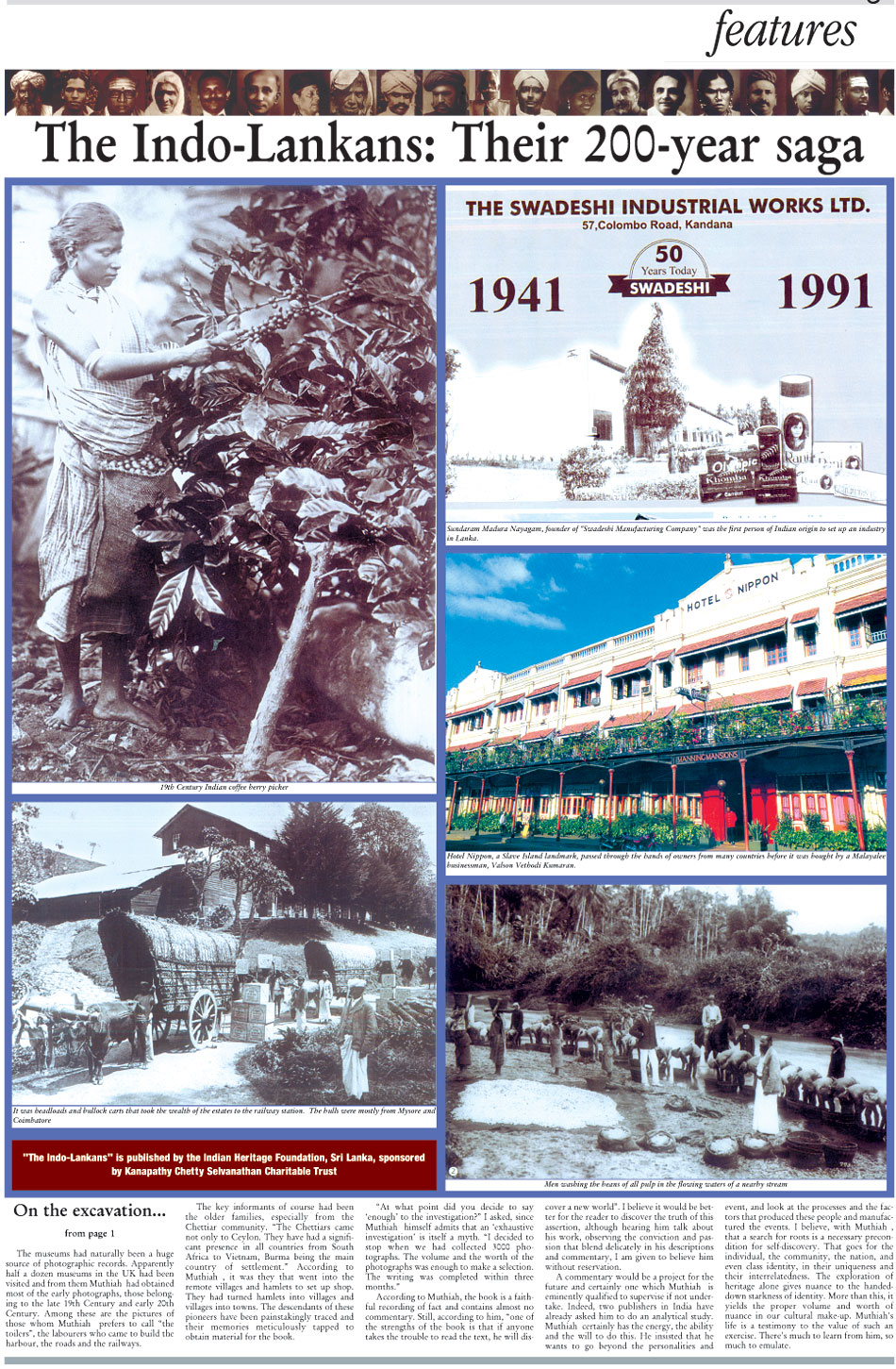

The museums had naturally been a huge source of photographic records. Apparently half a dozen museums in the UK had been visited and from them Muthiah had obtained most of the early photographs, those belonging to the late 19th Century and early 20th Century. Among these are the pictures of those whom Muthiah prefers to call "the toilers", the labourers who came to build the harbour, the roads and the railways.

The key informants of course had been the older families, especially from the Chettiar community. "The Chettiars came not only to Ceylon. They have had a significant presence in all countries from South Africa to Vietnam, Burma being the main country of settlement." According to Muthiah , it was they that went into the remote villages and hamlets to set up shop. They had turned hamlets into villages and villages into towns. The descendants of these pioneers have been painstakingly traced and their memories meticulously tapped to obtain material for the book.

"At what point did you decide to say ‘enough’ to the investigation?" I asked, since Muthiah himself admits that an ‘exhaustive investigation’ is itself a myth. "I decided to stop when we had collected 3000 photographs. The volume and the worth of the photographs was enough to make a selection. The writing was completed within three months."

According to Muthiah , the book is a faithful recording of fact and contains almost no commentary. Still, according to him, "one of the strengths of the book is that if anyone takes the trouble to read the text, he will discover a new world". I believe it would be better for the reader to discover the truth of this assertion, although hearing him talk about his work, observing the conviction and passion that blend delicately in his descriptions and commentary, I am given to believe him without reservation.

A commentary would be a project for the future and certainly one which Muthiah is eminently qualified to supervise if not undertake. Indeed, two publishers in India have already asked him to do an analytical study. Muthiah certainly has the energy, the ability and the will to do this. He insisted that he wants to go beyond the personalities and event, and look at the processes and the factors that produced these people and manufactured the events. I believe, with Muthiah , that a search for roots is a necessary precondition for self-discovery. That goes for the individual, the community, the nation, and even class identity, in their uniqueness and their interrelatedness. The exploration of heritage alone gives nuance to the handed-down starkness of identity. More than this, it yields the proper volume and worth of nuance in our cultural make-up. Muthiah ‘s life is a testimony to the value of such an exercise. There’s much to learn from him, so much to emulate.